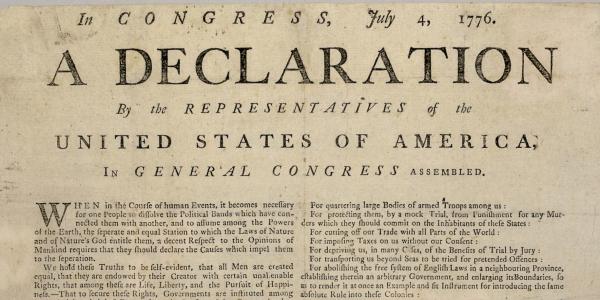

This Fourth of July, visitors to Washington University's Olin Library will have the chance to see a rare piece of history - an early copy of the Declaration of Independence known as the Southwick Broadside. Historian David Konig and curator Cassie Brand discuss the historical significance of the broadside, the process of conserving and displaying the document, and their hopes for the exhibition.

Transcript:

Claire Gauen (host): Thank you for listening to Hold That Thought. I'm Claire Gauen. We're doing a slightly different format today in honor of our Fourth of July episode. As our listeners may or may not know, especially in the St. Louis area, you can actually come to Washington University and see a rare copy of the Declaration of Independence. To talk about this document, I'm sitting down with curator Cassie Brand and law and history professor David Konig. Thank you to both of you for joining us!

David Konig: It's a privilege.

Cassie Brand: Thank you.

CG: So I hear that this copy of the Declaration of Independence is called the Southwick broadside. What is that exactly? Why does it have that name?

CB: A broadside refers to a piece of printing where it's printed on only one side of the paper, so you can think of something like a poster. Broadsides were often posted in public places in order to get news out. So, there are different nicknames for the different copies. The Dunlap broadside was the first one printed. Ours is called the Southwick Broadside because it was printed by Solomon Southwick in Rhode Island.

DG: That's a good way to put it. Their printed on one side because they're often plastered onto a wall in a public place, either outside a church, town hall, courthouse, or something like that. They were never intended to be permanent documents. That's why so few are left. Of the 200 or so broadsides that were published at the time, very few - fewer than a dozen and a half, I think - exist at the present. They were tossed away. But they were also read publicly, and that's the important thing to understand. We have to see that they are a revealing aspect of what was going on at the time, but also a revealing aspect of how popular mobilization works.

"Of the 200 or so broadsides that were published at the time, very few exist at the present. They were tossed away. But they were also read publicly, and that's the important thing to understand. We have to see that they are a revealing aspect of what was going on at the time, but also a revealing aspect of how popular mobilization works."

CG: Revealing in what way?

DG: Well, to understand the context of the time and how people would respond to it - why a broadside was so important to why Congress insisted and took such efforts - in fact, as you know, the text of the declaration was voted on on July 4th 1776. It was then sent to a printer in Philadelphia for copies to be sent on horseback to each of the individual now states, rather than colonies, to be read publicly. The purpose is to make sure that the public, who are now going to be a mobilized democratic populace, understand what is really going on and are not being misled by rumors. Rumors were very, very dangerous at the time and quite a source of fear. We might even compare them to fake Twitter feeds that we have so often today. To give you an example of this - in September of 1775, when the Congress was assembling in Philadelphia, news reached Philadelphia that the British fleet was bombarding the Port of Boston, that it was raining fire hell and brimstone on the people of Boston after actually an insignificant event at the time. A small British detachment raided an armory and confiscated some of the weapons that the militia had accumulated.

"Rumors were very, very dangerous at the time and quite a source of fear. We might even compare them to fake Twitter feeds that we have so often today."

But by the time the report of that episode reached Philadelphia, the fact that no one had been killed, that there were no injuries, was completely forgotten. The news reached Philadelphia and indeed much of the countryside around Boston was that seven men had been killed - how the number seven came up, who knows - and that the British fleet was now bombarding the town of Boston, killing men, women, and children indiscriminately. Well, any moment of thought would have revealed this to be a bogus rumor. Certainly because Boston was a haven for loyalists who were fleeing the patriot cause and were looking for protection under the guns of the British fleet, not to be massacred by the British fleet. Even so, tens of thousands of militiamen mobilized and marched on Boston to basically counter what the British were doing. Well, as soon as the news finally reached Philadelphia a second time - it took five days for the news to get to Philadelphia - the delegates, the Continental Congress, were frightened. They had left wives and children at home in Boston and were completely dreading the fact that their families may have been killed in this indiscriminate slaughter.

So it became necessary for the Congress, when the Declaration of Independence was voted on - that is to say when Congress officially now announced to the world what was happening - that no, shall we call them "fake news" stories reach the American people. It was then taken on horseback - to pick up the story - to Rhode Island, where Samuel Southwick, a local printer, ran off many copies of this to be read in courthouses and churches and so on across Rhode Island. By that time, it was necessary to do two things: One, to get the story straight and to have it be official, not just word of mouth. It was read publicly by town councilmen, by ministers, and so on, who were regularly recognized sources of authority and information. That's the important thing, too. The second is that the declaration, as you read it, is a very reasoned, cool, and logical type of argument. It is not intended to inflame wild emotion, which is often the case with rumor, gossip, or shall we say Twitter feeds these days. So we have to see it in its time as a document that was necessary to the the mobilization of a democratic populace to understand what was going on and why.

CG: How do you think people reacted to this broadside when it was first displayed in 1776?

DG: Well, I think they heaved a sigh of relief that Congress was taking the steps that they had expected - that it was not a wild, inflammatory indictment that would embarrass the Congress and just shall we say feed British hostility to the colonists as wild-eyed demagogues and Democrats. So I think there was a great sense of relief. We should also emphasize that it was read to the troops in the Continental Army, and this is a way to mobilize or to encourage and to draw them into an understanding of what politically and democratically was going on.

CG: So, hundreds of years later, this document came to WashU. Cassie, could you tell us anything about that story? How did it end up here?

CB: So I know that it was purchased by the Newman family, I believe in the 40s, if I'm remembering correctly. Rumor around the library has it that one of the family members actually carried it in a frame under his arm when he brought it in for donation. I love that story. It was hanging in their house for quite a few years before they donated it to WashU.

"Rumor around the library has it that one of the family members actually carried it in a frame under his arm when he brought it in for donation. I love that story."

DG: I'm sure that's a true story. It's fitting because that's how these ephemeral documents were treated at the time. In fact, if you look at it carefully you can see the folds in the document that we have that show how this was folded and thrown into a saddlebag.

CB: You can still see the folds, and there was actually some missing paper along those folds. You can see some holes along the top that may have been from hanging it somewhere. The physical document actually shows a lot of that history.

CG: So with that sort of damage, how do you go about conserving the document and displaying it, now that we no longer planning to fold it up and throw it in a saddlebag.

CB: No, we are definitely not allowed to fold it up anymore throw it into a saddle bag or carry it around under our arm! We actually sent it to the North East Document Conservation Center, the NEDCC, where they have experts in conservation who work on these kinds of documents all the time, and they did significant amounts of testing before they actually did any treatment. Some of the things that they did was use a dry brush to get rid of some of the dirt that had accumulated on the surfaces. They repaired the holes and filled them in and dyed the paper that they repaired it with to match the document. There had been some silk placed over the document in an earlier conservation treatment to help stabilize the paper, but that was removed in order to make the document clearer to read again. They flattened it, and they actually gave it a bath, which terrifies me a little bit because they submerged the entire piece of paper in water and an alcohol solution. They are experts, so they know what they're doing. I wouldn't want to submerge any paper in water! But they tested it first to make sure that it would hold up, and of course we're talking about early paper that's made from linen and cotton rather than wood pulp, so it holds up a little bit better to those types of treatments. But you can see the difference in the physical copy as compared to the digital copy we have on display. The digital copy was before conservation, so you can kind of do a side by side comparison in the case. Inside the case, we keep the light levels very, very low. We've had a lot of people comment on that. You have to let your eyes adjust a little bit before you can actually see the document, and that's to reduce fading - but also light can make paper more brittle. So we keep the light levels low; we keep the temperature and humidity very constant; we have monitors in the case that are making sure there's no fluctuations so that we can display it long-term.

"They flattened it, and they actually gave it a bath, which terrifies me a little bit..."

CG: So in addition to the document itself, you mentioned there is a digital copy. You can click on certain phrases and learn more. What excites you about presenting the document in that way with these new technologies?

CB: It's more interactive. We have the Declaration behind a large piece of glass, where you can't really interact with it. You can view it, which is really exciting, but you can't touch it and you can't play with it. The digital screen allows you to interact in a different way so you can learn more about certain phrases that were used, things that were taken out, the funny long S that looks like an F and how they were using it in spelling. You can also turn the document over in the digital version, which you can't do in the physical. So you can see how it's signed on the back, I believe it's the town of Warrick.

CG: When people come to see the document - either students who are here every day going through Olin library, or perhaps visitors who come specifically to see the Declaration - what sort of experience do you hope that they have when they see this document that probably most people don't see in their lifetime too often?

CB: I hope they'll get a sense of awe, like they're standing in front of history. The chamber has been designed in this really cool way. As you walk into this dark space, you kind of have to turn around so you can see it on display there in front of you. And you can get fairly close up to the glass, and the Declaration is not too far on the other side, so you can really get a sense of it. We also have an auxiliary case on the side, which allows us to do rotating displays of different smaller exhibits. Currently we have an exhibit on Jefferson's library on display. We have the third largest collection of Thomas Jefferson's books. And of course he is the author of the Declaration, so it's really nice to put his books next to his written work.

CG: What about you personally, encountering this document? You deal with rare books all the time, and David, as a historian you encounter rare materials - but the Declaration of Independence is something pretty special, I would think.

DG: It is, and as one of the editors of Jefferson's papers for the Princeton University Press, I work with his writing all the time. When I look at the Declaration, I look at it as I look at many of his other writings - which is that it goes through many drafts before it gets there. So it's interesting to see the original draft, which is available right here in our library in the Jefferson Papers collection. But it's also interesting because - Cassie made a good point that we're looking at history, and that means we're transporting ourselves into the past. We hope we're doing that. And the past, it's been said many times, is a different country. They speak a different language there, and a lot of the language in the Declaration has to be understood as of its time and place, of the 18th century. I think that's why the interactive quality of the exhibit, where people can actually touch the digital edition and can bring up commentary about it, is extremely revealing. When Jefferson says "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," happiness meant a little something different. It didn't mean fun. The English language is a very limited language, in that sense. I mean the French have lots of words for it - they can use plaisir, for example, or bonheur for happiness - but they also have the term felicite, which means wellbeing. And I think that's what happiness means in the Declaration. So if we can approach it better on its own terms now by seeing it placed in the context that the interactive display really permits.

"We're looking at history, and that means we're transporting ourselves into the past. We hope we're doing that. And the past, it's been said many times, is a different country. They speak a different language there."

CG: What about you, Cassie? Do you have any personal reactions?

CB: Well, I remember being just completely flabbergasted when I learned that there was a Declaration of Independence in the collection that I was responsible for. It was one of those moments where you're like, 'OK. this is big. I need to make sure that I learn more, that I know what I'm talking about for a podcast such as this, and that I can create an experience that allows people to stand in that room with history and really be able to learn from this document. And thankfully I have a wonderful team of people who've helped me with that, including Professor Konig. It was just one of those moments where I'm like, 'Oh! I get to be in the same room with this.' I've actually gotten to touch it.

CG: Really?

CB: Yes. Very carefully, very gently, trying not to sneeze or cough.

CG: I imagine that's very important! Is there any special programming coming up for Fourth of July, or events? Or are you just hoping people come visit?

CB: I think a little bit of all of that. We're actually closed on the Fourth of July, but we'll be open on July 3rd, and we'll be doing some programming, and we're hoping that people come to visit. We're still figuring out what exactly that programming is going to be, but hopefully we'll have a talk. I think we're going to do a display of some of our other items related to the Declaration and the founding fathers. We actually have one of George Washington's land deeds that was written by him, of course Thomas Jefferson's collection of books. I think we have an Alexander Hamilton signature. Those will be on display so that people can interact with them in a different way.

DG: The long-term benefits of this are considerable. I think it's good to have something that will bring people in and reveal to them what this library holds, how significant these things are, and what it can mean for their own appreciation of the past. When I would teach my Thomas Jefferson seminar, I made it a point to bring out the books that Cassie referred to, that Jefferson actually owned, and to let them feel them, pick them up, see his scribbles in the margins - which they are not encouraged to duplicate - and to understand that he actually held these. In fact, one of my speculations is that we have a copy of a book that probably he was reading the day he died.

CB: Professor Konig makes a really good point. The Declaration is behind glass, as are all of our exhibits, but in Special Collections we really encourage students and visitors to have a hands-on approach - of course with handwashing and completely drying your hands. We want the students to be able to interact with the books, to be able to turn the pages and to use the books as books, not just display objects.

CG: That's right. The library is not a mausoleum. What it has are artifacts that are to be understood as vehicles to understanding. And these books and the Declaration are not there to be worshipped. They are there to be pondered, they 're to be engaged, they're to be used. And I think the display that's out there is really a good gateway to that process.

"The library is not a mausoleum. What it has are artifacts that are to be understood as vehicles to understanding. And these books and the Declaration are not there to be worshipped. They are there to be pondered; they're to be engaged; they're to be used."

CG: That's wonderful, and I hope that all of our listeners come by and take a look - either coming up to the Fourth of July or sometime in the future. Are there any other comments that you like to share about this Southwick Broadside or the Declaration of Independence?

DG: Well, there's a lot of good literature on it. Danielle Allen has a wonderful book called "Our Declaration," which seeks to expand the scope of a document that has been seen as an assertion of white, male, propertied privilege. She has a different read on it that shows its significance beyond that. And David Armitage has a book on the use of the declaration by other countries, how often the wording in the structure has been copied - dozens of times by other nations, other peoples seeking self-determination. So it's an aspirational document. And those two books, just to begin with, really get you to understand what power words can have.

CG: Well thank you so much to both of you for talking with me and to Hold That Thought listeners. I really appreciate your time. Again, I encourage everyone to come take a look at the Declaration of Independence in Olin Library at WashU.

DG: Thank you.