From today's top 100 Billboard songs to ancient Sumerian scripts, human beings have always sung about love. So how have love songs changed across the ages? Have they evolved to reflect society's understandings of love? Or have we been singing about basically the same things for millennia? Today, we'll look at one batch of love songs called the Loire Valley Chansonniers, made up of five songbooks from fifteenth-century France. Clare Bokulich, an assistant professor of musicology at Washington University in St. Louis, explains why these books are so special and breaks down the rare insight they give into not only historical understandings of love, but music itself.

Transcript:

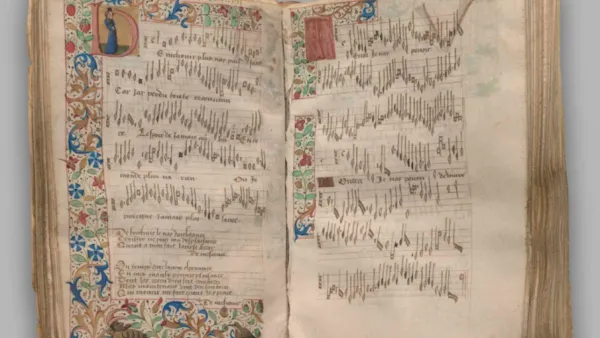

Rebecca King (host): Hello and thanks for listening to Hold That Thought! I’m your host Rebecca King, and today, we’re talking about love songs. Medieval love songs that is. And to consider the evolution of love music across the centuries, we’re going to look at on group of texts in particular, a group of manuscripts called the Loire Valley Chansonnier. Chansonnier is French for songbook. The 5 books that make up the Chansonnier were all produced in the Loire Valley region of central France between 1465-1475. In addition to the music and lyrics they contain, they are exquisitely illustrated, and each book is a unique object of art.

Given that recording devices wouldn’t be developed for centuries yet, these books offer a rare insight into secular music at the time, ranging from the courtly to the downright raunchy. So how have love songs changed over the last six centuries? And for that matter, how has music changed? Have love ballads evolved to match our own shifting understandings of love? Or have we been singing about the same sort of things for centuries, just to different tunes?

To answer these questions, and more, I met with Clare Bokulich, an assistant professor of musicology, who just taught a course on the manuscripts.

Clare Bokulich (guest): So these five manuscripts are a little bit different in terms of the make-up of which songs are contained in which manuscript and the kind of size and scope of the manuscript. But they have a lot of similarities. They are all very small manuscripts, and they contain mostly secular songs dealing with themes of love. Both the songs in the lyrics are written out in the manuscripts, and most of the songs are written in three vocal parts. So there’s a top part, a middle part, and a low part. If you want to look on the screen…

RK: So for you dear listeners, we do have scans of the books on our website for you to see what Clare is talking about, but in the meantime, I’ll do my best to tell you what they look like. At this point, Clare is showing me how the songs are laid out in the book, so if you were to turn to a song, on the top of the left page would be the music scored for the highest vocal range with lyrics under each line of music, matching notes to words—much as a song is scored today. However, from there, things begin to differ. On the bottom of the left page are two more verses for the song written out with no musical notation. Then on the top of the right page is the music scored for the tenor, or middle part but with no lyrics, and the bottom right page is the music scored for the contra-tenor, or the lowest part, but again, no lyrics.

So to perform these songs, the lower singers would have to sing the words included on the first page, but according to the musical notation on the second page. Today, if you were to look at sheet music, lyrics are written out below each part, and the parts are stacked so you can easily see in real time what the other singers are singing. However, this modern notation takes up a lot more space on the page to do this—three full pages instead of a single opening of the book, and so in a time when books were considered a luxury item for the very elite, making the most of the space available on every page was considered worth the inconvenience.

And the music notes themselves look different as you flip through the songs, according to the style of that particular scribe. One version of a quarter note looks almost like a pendulum with a diamond base and the line drawn from its apex. In the next song though, the notes are more rounded, like lines with little bellies on the bottom or the lower case letter d. And if that weren’t tricky enough, Clare notes that the musical notation is quite different than what we see today.

CB: If you're familiar all with musical notation, you'll see some different looking notes. First of all, the time signature and the clefs are different. And the note heads themselves are different. This is what's called mensural notation. Basically, unlike modern notation which precisely describes note values, if you look at this kind of notation, the rhythmic value of the note is dependent on its context. So, for instance, this is in a triple meter. This is basically a whole note, but the rhythmic value is chopped off by the following note. It actually decreases by one note value. So, this, instead of being three beats, is actually only two beats. It sounds more tricky than it is. Whenever I explain this to students, they're kind of just like, “That must be impossible. How could they have sung from that?” But with a little bit of training, it's actually quite simple in part because for the most part they follow particular rhythmic patterns, which, once you're used to them, are pretty easy for the eye to kind of parse.

RK: All right, so minstrels of the day wouldn’t have struggled to read the music. But who exactly was performing these songs? Actually, scholars aren’t sure that these chansonniers were ever meant for public performance, and much of this speculation is due to their size.

CB: We don't know exactly where the songs would have been performed, in what sort of context. So, we can try to piece together the kind of contexts in which they might have been performed just by looking at the dimensions of the manuscripts themselves. These are actually really small. If you opened out a manuscript, it would take up less than one sheet of printer paper, and they could actually be held in just the palm of one hand. So really, really small, which gives you some idea of the kind of detail in some of the images, which we'll talk about later. The small size of these manuscripts is in contrast to the ways in which sacred music circulated during the 15th century. For the most part, sacred music circulates in very large—what we call—choir book manuscripts. These are approximately the width of my arm reach. It would take two people to lift and to put on the lectern, and the singers in the chapel would gather around this large object and all sing from it. So, the images we have of this are people kind of huddled together singing from this one gigantic manuscript. This on the other hand is so small that you couldn't have very many people singing from it at one time. We tend to think of these as songs and being sung. It's possible that not all of the parts the vocal parts were sung. Some might have been played by instruments. The lower parts particularly could have been played by instruments, or they could have been sung. We don't know exactly how they were performed.

RK: Given the small size, the intricate illustrations, and the considerable cost of creating a book, which was considered a luxury item for the very wealthy in the 15th century, some scholars like Clare believe that it’s likely the books were given as wedding gifts or commissioned by very wealthy members of the French courts, and were never actually used in performance. But given their age, there are many mysteries surrounding the manuscripts.

CB: In terms of who created them and why, there are again a lot of question marks. We do know the dedicatee of one of the manuscripts, the Wolfenbuttel chansonnier, and the owner of that manuscript was a notary for the French royal court. So, someone who had a very established career, probably quite a bit of wealth. What gives us clues about the ownership to that particular manuscript is actually an acrostic. So, if you take the first letter of each of the titles of the songs, it spells out the notary's name, so Etienne Petite. And also his family crest appears in some of the images. So, there are kind of clues hidden in some of the manuscripts about who might have owned them, but for the other manuscripts, we can't really be certain.

RK: If we know so little about the people who owned these books, and why they were created, we know even less about those who actually penned the music. But Clare Bokulich and other scholars can piece together part of the story about how these chansonniers are connected just by the handwriting.

CB: Certain scribes worked on more than one manuscript. We don't know much about this one particular scribe who worked on a lot of the manuscripts, but what we do know is that he was very skilled and he had a very particular style. Just by looking at this one particular opening, I can tell immediately that this was the Dijon scribe. He liked to leave a space between the two lower voices here, and he was really meticulous about the length of the note stems, and he made them very precise, and he liked to do very long stems. So, it gives it this kind of spiky appearance, whereas if you look over here on the right for instance, you can see that there's no space between the two lower voices, and the note heads themselves are a little more rounded. Whereas over here, they are really spiky and angular. So there is some kind of characteristic things about his handwriting.

RK: These books, each copy, probably took 6 months to a year to make. Different scribes specialized in different aspects, from musical notation to illustration, so the manuscript had to be sent many different people before it could be bound and finished. This process certainly added to the cost of making these books, as did the simple material of the pages. It’s the fifteenth century in France, so the pages aren’t made of parchment. Can you guess what they’re made from?

CB: Something also to keep in mind that this isn't paper; it's animal skin. So, you can actually see on some pages it's really clear. You can see marks from the hair follicles. So, I can only imagine that it was pretty difficult to paint, and to paint such a level of detail. See this is a pretty good example, you can see kind of the patterning of the hide. The hair side is much rougher than the internal side, which is a lot softer and easier to write on.

RK: Was that typical?

CB: Yeah. Typical for this time period. Yeah, so that also gives you some sense of the kind of cost. I'm not sure how many—I think they were sheep?—how many sheep it would take, but not a small number, despite the small size of the manuscript. So, one of these manuscripts, the Dijon for instance, is actually, although it's very small dimensionally, it has hundreds of songs. So, it's really large in other ways.

RK: So now on to the music itself! Clare says that most of the poems in the book are written in forms fixe, which is literally a “fixed form.” These styles include the ballade, rondeau, and virelai, though most of the songs in the Loire Valley Chansonnier are in the rondeau form, meaning there is a repeating refrain followed some text in the middle that is sung to the same music, but the refrain text comes back at the end.

CB: So it's a very economical type of form. In performance, it can take anywhere from four to six and a half minutes to perform, but it is contained in a single opening of the manuscript. They worked from themes of courtly love, or what we call “fenimore.” These are poetic forms and poetic themes that have been established for already 200 years at this point. So, they're pretty well-worn, and what the poems usually feature is an unhappy and unrequited lover who is kind of extolling the virtues of the one that he loves. It's usually a male speaker and a female object. They kind of play with a lot of the same themes. So, he often describes the merits of his lover, but also describes his unhappiness at the fact that he can't physically be with her.

RK: Want to hear what this song sounds like? Here it is.

CB: This is translated from the French, and it's in a rondo form. So, the poem reads, “My mistress has such great merit that everyone owes her tribute of honor, for she is in virtue as perfect as ever was any goddess. When I see her, I feel such joy that there is paradise in my heart, for my mistress has such great merit that everyone owes her a tribute of honor. I do not care about any other riches than to be her servant. And because there is no better choice, I will always carry as my motto, ‘My mistress has such great merit that everyone owes her tribute of honor, for she is in virtue as perfect as ever was any goddess.’” So, these themes of unrequited love and the mistress having such great merit, these are themes that come up in the majority of the poetry from these manuscripts and perhaps you could hear that the way in which the refrain comes back at the end and parts of the refrain are actually strewn throughout the poem. So, it's kind of segmented that way.

RK: Sounds just like Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me,” right? Or REO Speedwagon’s “Can’t Fight This Feeling?” Okay, so not on the surface. But the premise is still the same. And given how popular unrequited, or courtly love songs were, even 600 years ago, people apparently got sick of hearing about it. Soon enough, there came parody songs making fun of the form in the Chansonniers as well.

CB: By this point, a lot of the kind of themes had been worked out, and poets and composers found ways to sort of play with these forms and play with the themes and topics of courtly love. So, another example is this rondeaux, and it explores the relationships of this type of poem particularly by using the power of the refrain. So, the poem goes, “Not that I'd want to think of anything but well and faithfully loving her who surpasses all others and be just a bit in her favor to have my name and improve my lot.” So, the end of that refrain is a little bit edgy, but it's not entirely unfamiliar in this kind of poetry for the speaker to want to improve himself through this type of unrequited love. So, the poem continues, “To her service and honor I would dedicate myself completely as long as I gain something by it.” But then the refrain interjects, “Not that I'd want to think of anything but well and faithfully loving her who surpasses all others. Her gentle sweetness, which has no peer, pleases in my heart unceasingly, and so much that it wants to live and die as hers, and I will do so whatever else I may accomplish unless I manage to forget her. Not that I'd want to think of anything but well and faithfully loving her who surpasses all others and be just a bit in her favor to have a name and improve my lot.” So, the way in which the poem as all rondeaus end with the refrain, it's using it to kind of drive home this cheeky reading.

RK: And finally, let’s not forget the well, raunchy, love songs. That’s right, Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On” or Ginuwine’s downright dirty song “Pony” have a 15th century equivalent. Just a quick warning that the next song is pretty sexually explicit and includes some expletives, so if that’s not your thing, you might skip to the end.

CB: On the other kind of end of the spectrum, at the end of one of the manuscripts, there are a few songs that have two or three different poems sounding at once. So, the top always typically has a courtly song in one of the styles that I just read. Whereas the lower voices have a popular song, and that means that both the style of the music is very different. It's usually much more angular and repetitive, and the melody might jump out of the texture a little bit more. Whereas the top voice is more syncopated, it's more complex. It's more kind of rhythmically and melodically ornate. So, there's one particular song from the Dijon manuscript, and there are three tracks sung all at once. So, the top voice sings, “Body against body without being greedy. To love one another straight from the heart. To do the deed always in secret. This should be the custom of lovers. Without demanding too great a reward but to come together joyously from time to time. Body against body. There should be no dissembling in true love, and each should behave in an honorable way. A lover has nothing to do with money. If he can keep his lady according to her humor, body against body.” So already you get the sense that this is kind of a little bit different because it’s mentioning bodies, which is something that the most courtly poems don't mention.

CB: Then the middle voice is a shorter text, and it sings, “The arse owes the cunt five and a half shillings on St. Remigius’ Day. So, she's allowed five and a half shillings for the psalms and the evangels, and the arse has fun for her.”

CB: So, then the lowest voice gets even more racy. “Stuff her up, cobbler! Stuff up her stocking. I met a little nun who fell down with a crash. I laid her down on the grass and took off her habit. Stuff her up, cobbler! Stuff up her stocking. Press the tired arse, gentle partner. Press the tired arse, sweet sergeant with the staff. Balls of iron and cock of lead and cunt of steel. I was returning from Noyon, balls of iron and cock of lead, where I met a young fellow. Hey you! You! Yes, yes, yes. Bold of arse, pull yourself out there. Saucy wench, put your arse on mine. I'm coming. I'm holding, saucy fellow.” So, these are three poems being sung all at once in three different kind of styles, both melodically and poetically. So, that gives some idea about the kind of spectrum of songs that we're dealing with in these manuscripts.

RK: So what does all of this tell us about love music in the fifteen century and over the centuries? Clare Bokulich brings it all home.

CB: One thing we can say is that the way in which women are portrayed in a lot of these poems, particularly the courtly ones, like the first one I read “My mistress has such great merit,” is in contrast—that's putting it lightly—to the day to day reality of women in the 15th century. So, it's very much this imaginary ideal about love. One of the things that the students have caught on to is the very hyperbolic nature of the poems. They've talked about some similarities with lyrics of popular music today, the use of kind of hyperbole and exaggeration to express themes of love. One category of popular song today is of course the breakup song, and I can't think of any 15th century equivalent to that. But we certainly get a similar kind of spectrum of songs in popular music today from unrequited love to the more kind of raunchy, obscene song. I think ultimately people are always going to sing about love. It's not about to die out.

RK: Many thanks to Clare Bokulich, an assistant professor of musicology at Washington University in St. Louis, for taking the time to talk about the Loire Valley Chansonniers with us. And thanks to you too for tuning in to Hold That Thought. Let us know what you think of today’s episode, and your favorite love song, but finding us on Facebook or Twitter.

Credits:

Audio "Dictes moy toutes voz pensees," "au travail suis sans espoir de confort," "corps contre corps."

*Note: the translations of the songs came from the following sources.

-Leeman Perkins and Howard Garey, The Mellon Chansonnier, Vol. 2 Commentary

-Emily Zazulia, "'Corps contre corps', voice contre voix: Conflicting Codes of Discourse in the Combinative Chanson," Early Music 3 (2010).

-The Copenhagen Chansonnier and the Loire Valley Chansonniers: Edited and Commented by Peter Woetmann Christoffersen http://chansonniers.pwch.dk/