While Shakespeare wrote his plays, English theater itself was changing. The first actual theaters like the Globe were built, so companies could perform in places built solely for performance rather than marketplaces, pubs, or inns. Instead of religious and morality plays, writers brought politics, race, and class issues to the stage for the first time in London, which made authorities wary. Musa Gurnis, an associate professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis, explains what early modern theater was like for London audiences and how theater gave English society a way to think about itself in a new way.

Transcript:

Musa Gurnis (guest): One thing that really interests me is the process of performance, that theatre is an art that happens collectively and in time. I think there is something important and special about that kind of real-time shared experience of an audience from really mixed class and cultural backgrounds sharing fantasy.

Rebecca King (host): Hey there listeners! Thanks for tuning in to Hold That Thought. I’m Rebecca King, and today, we’re delving into Shakespeare’s world to look at what theatre and the theatre going experience was like at this time.

MG: My name is Musa Gurnis. I am an assistant professor in the English department here at WashU, and I work on English commercial theatre in the late 16th, early 17th century.

RK: Musa is currently writing a book on early modern theatre in London, and she was kind enough to meet with me to discuss this era in theatre history. So what is early modern theatre? What are it’s states and hallmarks?

MG: The start is harder to set than the end date. I mean the theatres close in 1642, not as is commonly thought because Puritans hated theatre—and actually that’s one of the interventions I make in my book. I show positive forms of Puritan engagement with theatre culture. But mostly they closed in 1642 for crowd control safety reasons during war, but that’s an end date.

RK: For those out there like me who are a little rusty on their British history, 1642 is the year the English Civil War began, and Parliament fought King Charles I for control of the government. But that’s getting pretty off topic. Let’s return to the theatre.

MG: There was commercial playing in inns like The Red Lion as early as 1567, but the first purpose built commercial theatre, right like were going to invest and put up timber just to do this new kind of representation, that’s 1576 with Burbage’s Theatre. It’s called just The Theatre.

RK: Before, Medieval theatre was held in open market places or churches, and morality plays were the go to, where a protagonist meets personifications of various vices or virtues to teach viewers a moral or lesson, which was often religious. However, during the early modern period, the first actual theatres were built in London, including the famous Globe Theater, and theatre itself became a competitive business much like the film studios we have today. Plays and characters also became more complicated and more morally grey to reflect real-life politics and popular culture at the time.

MG: The theatre really had an intensely symbiotic relationship with the surround culture and a mutually productive one. It’s not just that what they were doing is reflected in these plays. Plays that really put politics on stage for a mixed class, mixed gender, popular audience. So you didn’t have to be literate or able to read Machiavelli or able to read Holinshed’s History of England to be able to think about questions of sovereign power, the state and the people, and so on in sophisticated ways. That kind of specific, political, and cultural engagement, and also, I mean it’s a business; those people were really paying attention to the market. Medieval theatre also has forms of commercial engagement like the carpenters are doing the play of the crucifixion and the tapestry makers are doing Pilot, who’s all decadent and sleeping, but it’s a form of advertisement. So it’s not as if early drama is untouched by the market, but what you see that is distinctive in the early modern period is a competitive theatre business that works much more like the contemporary movie studio system—you know, the way we have Fox and Miramax will both be coming out with a dark superhero movie, right? We’ll see people sort of imitating popular figures. After Tamburlaine comes out and it’s this crazy success, there are all these poor man’s Tamburlaine plays where someone will do a spinoff of the Tamburlaine character or a serialization or something like that, not just within companies but across companies. They’re really attuned to their market.

RK: Shakespeare’s history plays fit into this idea that politics and real class issues were finally being brought to the stage during this time in London. And despite what some would say, Gurnis maintains Shakespeare’s histories are not at all propaganda for the Tudors. They’re actually more complicated than that.

MG: I don’t think Shakespeare’s a Tudor apologist. I think the history plays have what we call a hermeneutics of suspicion, an unmystified, unsentimental examination of how power works at the very highest levels. When you compare it to something like Heywood’s If you know not me, you know nobody Part II—no, Part I—which is a hagiography of Elizabeth that’s basically “Ra Ra Elizabeth! Here come the protestant Tudors! Hooray!” what Shakespeare’s doing is much more critical. I mean, it’s the kind of real political analysis that you get in continental prose works that you get in works like Machiavelli’s The Prince or something like that. Very often in Shakespeare’s plays you’ll get the most pious and correct expressions of the legitimacy of royal authority coming as total manipulative propaganda out of the mouths of villains. Like Claudius in Hamlet who’s murdered the king, when Laertes comes in and threatens to kill him, he’s like, “Stand back. There’s such divinity doth hedge a king / That treason can but peep to what it would.” He’s like, “Don’t worry. I’m an anointed king. No one could ever kill me.” Obviously, that’s total spin, and that’s usually the ideology of sacred kingship that usually appears in Shakespeare’s plays as propaganda.

RK: It’s also important to consider how people thought about the theatre in this era. As Gurnis explains, many religious and political authorities saw it as a threat to society’s virtue and civil obedience.

MG: There is always concern from the city fathers that these large gatherings of unsupervised people are sort of a security risk, or in times of plague, everyone’s worried that they’ll catch infection. I mean, that seems like a legit health concern, right, but no one’s saying, “No, you shouldn’t go to church or else you’ll catch the plague.” The theatre is often decried as this sort of morally dodgy place full of prostitutes and pickpockets, where you see all kinds of treasons and infidelity. If you’ll learn how to murder kings and sleep with your neighbor’s wife, you know, great, go to the theatre. But also there are people really defending theatre’s sort of socially familiaritive value. Thomas Heywood, who is a playwright, writes the great defense of theatre called the Apology for Actors and he’s like, “Look. This is the school of English bravery. This is where we see these foundational stories of our nation. It teaches political obedience because villains die in the end.” He definitely asserts a kind of moral clarity for theatrical representation that I think doesn’t exist. He does defend theatre as something that has a positive social value.

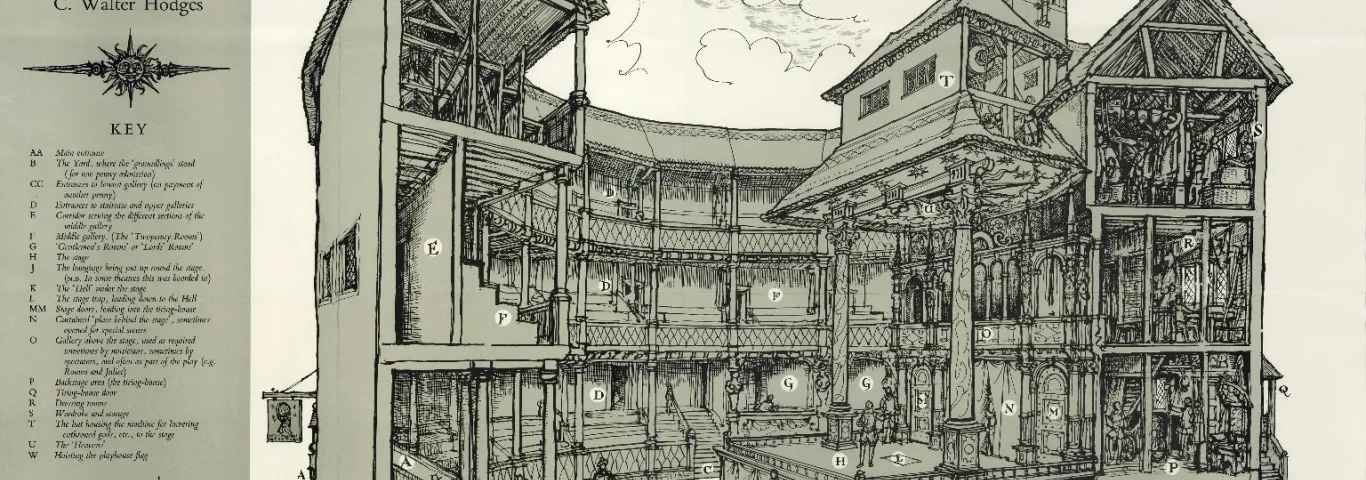

RK: So what were these early theatres like? Musa Gurnis says that as the business grew and evolved, so did the buildings.

MG: In the beginning, they built these amphitheater theatres like the globe. You pay a penny to get in and stand and be a groundling. You pay two pennies to sit down and three to sit down with a cushion. It’s definitely with in the price range of not very poor people, or course, but of apprentices and so on. They could definitely go see those plays, go see Shakespeare, go see Marlowe, go see all of that. But then you get after 1609 or so, after that first decade, there is a sort of splintering of that theatre. There is a more elite theatre. You get companies playing in more exclusive, more expensive, what they call private theatres, like Black Friars, but you know, for example The King’s Men, Shakespeare’s company, they play the same repertory at the Globe and Black Friars. And it’s not as if after these more exclusive, private theatres are invented that upper-class men stopped going to The Globe. It was a major public monument. It was a source of civic pride. It was something that put London on the map. There was nothing else like it in England.

RK: How these were acted out is also something different from what you’d see today. Gurnis says that the average touring company was fairly small, made up of core-players who would have to fill multiple parts in each play. Remember too that women were not allowed on the stage at this time either, so boys would have to play all the women’s parts. Attending a play as an audience was also a pretty different experience than it is today.

MG: I mean, this is totally fascinating. What we know about the conditions of playing is that they are very varied. We get descriptions of riots, which was always the fear of the authorities: the gathering, this many people unsupervised by religious or state authorizes in one place was dangerous. And there were a few apprentice riots that did start in theatres. We know sometimes there was heckling or fighting amongst people in the crowd and the audience could be quite rowdy, not this super civilized, bourgey playgoers that are Shakespeare’s primary audience today. But also, it’s not as if they are rowdy all the time. You also have these descriptions of intense hushes, and sometimes on holidays or May Day, it would be packed and audiences could vote up or down on the play. They’d play it the first time, and if they loved it they’d keep it and if they didn’t, some things got squashed. Obviously, in the globe, the open-air theatre, there is mutual visibility: they’re playing in the day, so the actors can see the audience; the actors can see each other. For me, something that is really distinctive about theatre of this period is the audience is built in to so many plays wither as an extension of a non-stage crowd or more subtle kinds of meta-theatre that really have an eye toward audience experience.

RK: Finally, I asked Gurnis how special Shakespeare was by virtue of the fact that he was both an actor and a writer. She explained, though, that writers who were also actors were not all that uncommon in early modern London.

MG: He wasn’t the only writer-actor. Johnson acted, too, for example. Shakespeare’s an unusual case in that half of all plays in the period were written collaboratively. Shakespeare more often wrote on his own. Sometimes playwright had a particularly strong connection to a particular company, but most of the playwrights were kind of writing on the specs, selling a script to whoever wanted it. Shakespeare was literally his own boss, which is highly unusual for a playwright in the period. He was a sharer—an owner—of the company that he wrote and acted for. So he had a position of unusual stability. Nothing in the theatre is every autonomous. It is just skin to bon, all collaborative all the time, but he was the leading playwright of the leading company who mostly wrote on his own. He had some degree of artistic autonomy that not everyone had.

RK: So in many ways, the early modern English theatre was the birthplace for the theatre that we know today. Real issues of contemporary culture were played out on stage for the general public: crowds of all classes, races, and genders. As Gurnis said in the previous episode, “Why Shakespeare?” the early modern theatre gave London a place to think about itself. And if you think about some of the plays from our contemporary theatre, The Crucible, A Raisin in the Sun, A Streetcar Named Desire, Angels in America, isn’t that what theatre does for us, too? Many thanks to Musa Gurnis for taking the time to meet with me, and thanks to you, too, for tuning in. Like what you heard today? Subscribe to Hold That Thought on Soundcloud, ITunes, or Stitcher to keep up with our latest episodes.

Credits:

Archive.org The Music of William Byrd Played by John Sankey